When we think about mime, we often bring to mind a performance that includes the use of gesture, silence and perhaps the wearing of a mask. However, mime has taken many forms over the centuries and millennia of its existence and much has been added and taken away from mime over this period.

This article takes a look at the fascinating story of mime, from its ancient origins to its current place in a postmodern world.

Mime’s Ancient Origins

Where did mime first originate?

Pinpointing mime’s precise origin is impossible since early forms of mime predate writing and an agreed upon definition of mime doesn’t exist. However, it is widely accepted that the Western mime tradition was born in the villages and rural areas of Ancient Italy and Greece and formed part of the festivals in honor of Dionysus and other Greek gods.

Mime was a very controversial art form from the start and was often seen by the ruling class as a subversive influence on society. Unlike traditional Greek plays, mimes featured both men and women and were performed by both professional and amateur troupes. Popular subjects included adultery and other vices and mimes often involved mythical characters such as Herakles and a host of generic ‘stock’ comedy characters (old hags, foolish slaves, incompetent doctors, etc.) These performances were largely improvised and were epitomised by the bawdy Dorian mimes performed in the Greek city of Megara.

Although these early mimes mainly used gesture and dance to convey their stories, they were far from silent, making full use of music, song and even spoken verse. The mime artists would in fact often parody other people (the latin word ‘mimos’ means to imitate and is the origin of the word ‘mimic’).

Mimes were also used during ancient Roman funeral rites where actors would wear masks resembling the face of the deceased and their ancestors. The size and extravagance of the funereal processions were seen as an indicator of the importance of the deceased and their family in society.

As the Greek traditions moved northwards over time, mime took on different forms but generally stayed true to the dance and burlesque tradition. For example, the Phylakes (Gossip Players) of the 4thand 3rdCenturies B.C. mixed figures from the Greek pantheon with stock characters from Greek comedy. Herakles retained his popularity with Odysseus another favorite character of these farces.

The Phylakes – also known as hilarotragedies – tended to portray gods and semi-divine characters alongside humans in mundane adventures with plenty of lewd activity throughout.

Costumes and props were simple and symbolic and masks made a return. Just five authors of this art form are known by name: Blaesus of Capri, Heraklides, Sopater of Paphos and Rhinthon and Sciras of Taranto.

Meanwhile, a distinct pantomime movement was developing. Pantomime performances were distinguished by both their appearance and their subject matter. The central character (pantamimos) would wear a mask with wild hair, closed mouth and gaping eye holes, presumably to make it easier to convey expression through the eyes. Pantomimos, dressed in a long silk tunic and sporting a pallium as a prop, would silently act out tragic librettos (like Virgil’s tale of Dido and Aenead) using gesture and cheironomy (hand movements). His or her role was to interpret the story as sung by the soloist or choir.

Pantomimes were usually accompanied by an orchestra of wind, string and percussion instruments and the first pantomime actor ever recorded was the dancer Telestes who acted out scenes from the 5thCentury play ‘Seven Against Thebes’ by Aeschylus.

The Rise and Fall of Mime in Rome

Pantomime had already evolved into an established art form before taking a more literary turn during the era of Julius Caesar. While Pylades of Cicilia is credited with developing tragic mime in Rome around this time, Bathallus of Alexandria is associated with comedy.

As pantomime grew in popularity under the Roman Empire, it began to replace the Atellan Farce (which had incorporated the Phylakes tradition during the early Imperial years) as interludes on theater stages. It also became the only dramatic event at the annual Floralia festival.

With the exception of Emperor Trajan, who banned mime artists, most emperors embraced the tradition. Mime flourished under Augustus, the first Roman emperor and Nero (last of the Julio-Claudian emperors) even practised the art himself. During his reign, Marcus Aurelius went as far as to dedicate mime actors as priests of Apollo.

The rise of the Christian church would bring this golden period of mime to an end. Unhappy with the nudity, anti-Christian satire and occasional real on-stage executions, the church eventually clamped down on performances, excommunicating all mime artists in the 5thCentury A.D.

Mime Through the Middle Ages

Over time, the church relaxed its stance on mime and the art form began to re-emerge in the guise of mystery and morality plays. These used the personalization of virtues and vices to teach moral lessons.

Mime also survived within the courtly shows and pageants which initially emerged from the Duchy of Burgundy in the 9thCentury before developing into the intermedios of the Renaissance period and, later, the courtly masques.

16th Century Dumbshows – A Brief Flowering in England

Meanwhile, over in England, the morality play had evolved into the silent dumbshow, a supplementary performance shown during the interlude of a play. Popular 16thCentury plays in which dumbshows played a significant part included The Battle of Alcazar; Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay; Gorboduc; The Old Wives’ Tale; The Spanish Tragedy, and a Warning for Fair Women.

Sometimes, the dumbshow foreshadowed the action to come in the main play. This was the case in the most famous occurrence of the dumbshow within the Shakespearean play Hamlet where Prince Hamlet and a group of players perform the show for King Claudius. Shakespeare also included a dumbshow as a major part of his 17thCentury play, Pericles, Prince of Tyre.

By this time though, dumbshows were already fading out of fashion and disappeared from the mainstream scene shortly afterwards, resurfacing occasionally within courtly masques.

From Italy to Paris: the Birth of Pierrot, the White Clown

In Italy, the street performing tradition that came to be known as Commedia dell’Arte is thought by many to have its origin with the Atellan Farce. Commedia dell’Arte produced four groups of characters known as the Capitani (captains), Innamorati (lovers), Vecchi (old men) and Zanni (servants).

These groups became diversified into specific characters of which the Zanni Arlecchino is among the most recognizable, becoming the jester-like Harlequin. Another character which grew to prominence in the 17thCentury and is now almost synonymous with mime is Pierrot, the tragic, white-faced clown who pines for the love of his wife Columbine only to lose her to Harlequin.

Pierrot originated with a Comedie-Italienne troupe in Paris but became identified with one man in particular, the Bohemian-French mime Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796-1846). The son of a French soldier-turned-showman father and Bohemian servant mother, Deburau first started performing as Pierrot at the Theatre des Funambules at the age of 20. His shows were so impressive that notable poet and critic Theophile Gautier referred to him as, ‘the most perfect actor who ever lived.’

He also reinvented the character, turning him from a course and stupid figure to a courageous and clever one. In fact, Deberau created several subtle variations of Pierrot depending on the theme of the pantomime he was presenting. He also changed Pierrot’s dress to help free up his body and reveal more of his face, replacing the traditional white hat with a black skullcap.

Deburau’s Pierrot became the blueprint for all Pierrots to follow, adapted to fit the purposes of all the various cultural movements of the next 200 years.

Jacques Copeau: The Man Behind the Mask

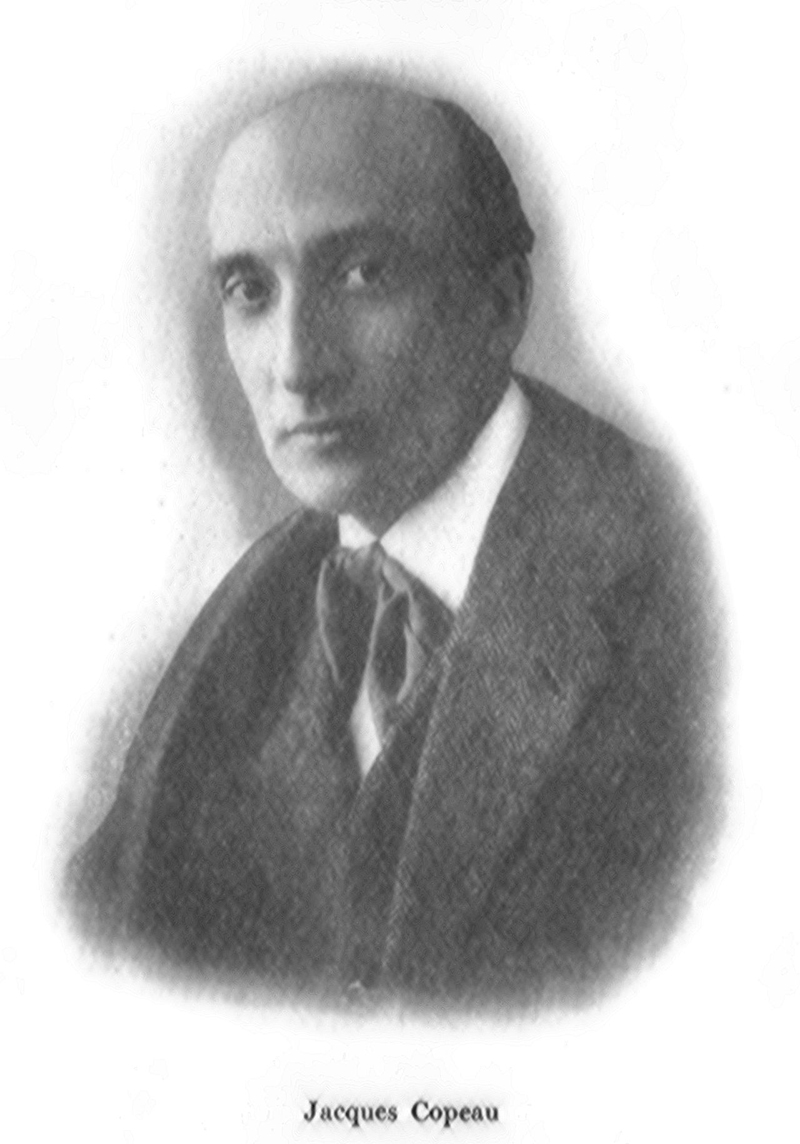

The Commedia dell’Arte tradition (as well as elements of Greek theater and Japanese Noh and Kabuki theater) also heavily influenced the work of Jacques Copeau, a theater critic who went on to found his own theater and acting school in the 1920s.

Copeau wanted to move away from the popular theater of the time and return to the basics of the art, the human body. He disliked the tricks actors used in popular performances and despised ham acting. His idea of theater was grounded in simplicity of design and the technical skills of the performers. He achieved this distance from the mainstream, practically and symbolically, by founding his Theatre du Vieux-Columbier on the Left Bank of the Seine.

Copeau’s school included the art of mask construction. At a time when psychoanalysis was becoming popular and the world was descending into the madness of war, the mask was seen as a way to connect with, express and even balance internal impulses.

Unlike the grotesque and exaggerated masks of early mime though, Copeau was interested in creating the ‘neutral mask.’ This would enable the actor to strip away their existing idiosyncrasies and allow then to express their gestures fully and authentically.

Copeau’s importance to the world of mime and theater in general cannot be overstated. It is most aptly summed up in the words of Albert Camus: “In the history of French theater there are two periods: before Copeau and after Copeau.”

One of the most renowned students to come out of the Copeau school was Etienne Decroux. While Copeau’s work was broad, encompassing all aspects of theater, Decroux’s focus was solely on the actor’s use of his or her body. From 1946, he dedicated his life to corporeal mime, seeking to free the actor to express their ideas and ‘make the invisible visible.’

Decroux was determined to spread his methods worldwide and influenced not only theater but dance and circus arts too. He is sometimes referred to as ‘the father of mime.’

From the Streets to the Studio

The traveling theaters and circuses of the late 19thCentury were to have their influence on the silent film era which was just beginning to take off. They inspired a young Gabriel Leuville to turn his back on his parents’ vineyard business and become a film actor. His ability to convey expression with a rare subtlety saw him rise to the top of his craft under the name Max Linder and his character Max the incompetent dandy.

Max Linder, in turn, influenced one of the most renowned and commercially successful figures of the silent film era: Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin helped re-establish the art of mime across the world and his work continued to bring in the crowds even during the early days of the ‘talkie’ which reduced the need for physical mime.

Chaplin refused to talk much about his techniques, claiming that to do so would be similar to a stage magician explaining their tricks. His abilities certainly enchanted a young French boy, Marcel Marceau, when he was taken to see a Chaplin movie by his mother. He first used the art of mime not as a form of entertainment but to help Jewish children remain silent as they were moved out of Nazi-occupied France to Switzerland.

After World War II, Marceau joined Charles Dullin’s School of Dramatic Art in Paris where he was taught by Etienne Decroux among others. Nevertheless, he had more affinity with the mime performed by Deberau and characterized through Pierrot. Marceau became famous for his Bip the Clown character and for his various mimed exercises. These included the ‘Walking Against the Wind’ exercise which he learned from Decroux. Decroux also taught the exercise to David Bowie and the move bears an uncanny resemblance to Michael Jackson’s Moonwalk. Jackson once planned to collaborate with Marceau and admitted to being ‘in awe’ of his performances.

Marceau referred to his performances as practising the ‘Art of Silence’ and toured extensively to spread his art as wide as possible.

A New Direction

Despite Marceau’s talent, the art of mime was in danger of becoming restricted once more to the silent, white-faced clown. The time was ideal for a change of direction and Jacques Lecoq provided it when he established the Ecole Internationale de Theatre in 1956.

Lecoq’s background was in sports education and he had a keen interest in sports performance, particularly gymnastics. He also developed an interest in acting through friendships with well-known actors such as Antonin Artaud and Jean-Louis Barrault. He was also introduced to the work of Jacques Copeau through Copeau’s daughter Marie-Helene and her actor-director husband, Jean Daste. Daste taught Lecoq about the Japanese Noh tradition, sowing the seeds of his fascination with masks which would form a central part of his school.

Following the end of the Second World War, Lecoq taught in Germany and Italy and became familiar with the techniques of Commedia dell’Arte and the masked choral tradition of Ancient Greek tragedy.

He combined elements of all of this in his new school which admitted 90 students per year and sought to teach students a performance language which emphasized the bodily movements of the actor. His school focused on physical performance and the philosophy of movement and encouraged improvisation, collaboration and openness. Lecoq insisted that each student had to find their own actor within as each would hold different tensions and respond in unique ways.

Lecoq used a series of masks to help with this discovery process, starting with a neutral mask and ending with the clown’s red nose. His school popularized the full scope of mime for a new generation, from clowns and harlequins to melodramas and tragedies.

Mime in Modern Times

If Marceau’s popularity risked restricting the definition of mime to stifling proportions, the students of the Lecoq and Decroux schools and their diverse companies have led to a concept of mime that defies description. For example, the ‘total theater’ of Jean-Louis Barrault sees the voice as every bit as important as any other part of the body, breaking the link between mime and silence.

The influence of postmodernism has led to a blurring of all artistic boundaries with elements of mime, clown art and Commedia dell’Arte apt to appear alongside contemporary dance, theater and puppetry. There has also been a tendency to label any non-literary, visceral performance art as physical theater and any non-traditional mime act as new mime or postmodern mime.

Whether mime is set to carry on becoming absorbed and commingled with other art forms or whether new distinct styles will emerge is unclear. What is more certain is that the long and varied history of mime will continue to fascinate and inspire both current and future artists for a long time to come.